Black worldviews sown across the Western countries now show their fruits specially in the arts. The different artistic languages, for being connected with the intuition and the soul of the one who expresses through them, are sources of emotional development. Emotion has been the key gateway to ‘Afroseed’ Brazil. It is not a mere coincidence that our expressions of affection are marked by lexicons borrowed from bantu languages: dengo [treat], cafuné [cuddle], xodó [the apple of one’s eye]. The Brazilian arts are largely made up of cultural blackness. But in Africa, unlike what the West proposes, the arts are inseparable from everyday life, which, in turn, is imbued with the sacred. The African knowledge incorporates it all.

To go beyond the simple fact of carrying a dark skin and bear with all that it entails, ancestrally-black intellectuals develop matter (body) and non-matter (spirit) of which we are made simultaneously and communally, without having the brain (and the ego) leading the way. To this end, it is fundamental to keep the senses working permanently (touch, smell, taste, sight, hearing) and the memory (which is not only in the head, but in the whole body): what is experienced, role-played, performed is learned/understood – see the expression coined to designate the “pop culture events” as being major sources of black knowledge handed down between generations. In black worldviews, thinking and feeling are inseparable. “Where the chicken lays her eggs, there she will keep her eyes on,” says the ancestral wisdom.

But we, westernized, unlearned about integrating mind-body-soul that is typical of the worldview of the peoples deemed “undeveloped” or “stagnated.” Taking into account the 18th century enlightenment Cartesianism and the proposition of one single civilization/mankind standard to follow (the Euro-Western-Christian), we overvalue reason. And, with it, a single way of thinking prevails; what prevails, for example, is the Western allopathic medicine as opposed to the medical practices that see the human being in its entirety, such as the Chinese or the Indian medicine, and the notion of traditional health (physical, mental, spiritual) and healing originally from the Americas seen in what was hierarchically called traditional knowledge (which have not obtained the epistemological status discussed by Nilma Lino Gomes) and in afro-indigenous-Brazilian religions. The colonization of our minds and our bodies by this single way of thinking makes each of us potential breeders of racisms – in the plural, as proposed by Stuart Hall – and other fundamentalisms.

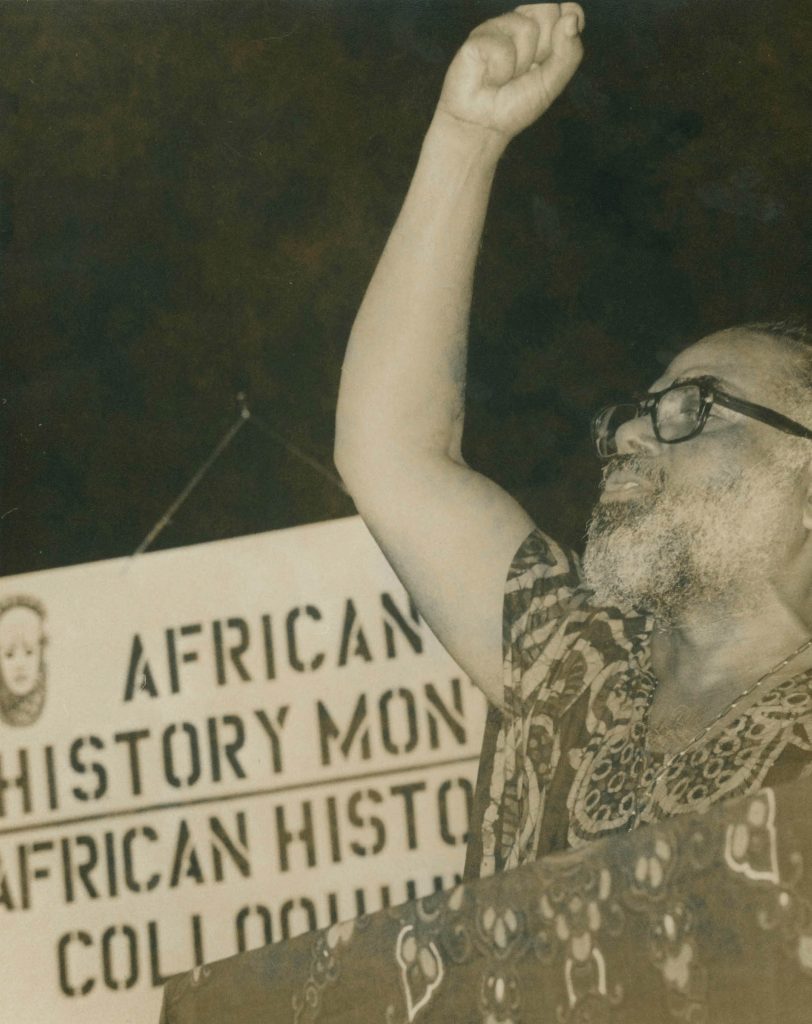

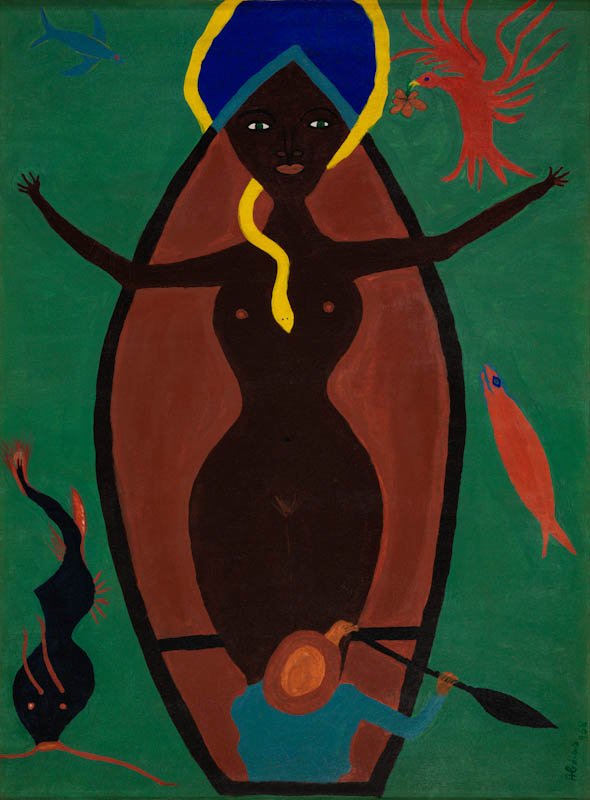

The circular reading of the universe proposed by the African worldviews sees all kingdoms (mineral, vegetable, human) as interdependent and sacred carriers (which is not separated from the visible world, like in the Euro-Christian perspective). Manipulating elements of nature is healing for the soul. Making art is to integrate the sacred human – body, mind, and soul – to the other sacred elements spanning vibration, rhythm. The arts encompass the principles of other disciplines – philosophy, geometry, physics – very compartmentalized by the West. Abdias is here taking part of this Afro-diaspora that shares the nature-cosmos-culture continuum and the circularity for its civilization value and that brings together non-compartmentalized disciplines. Like him, there are intellectual blacks from elsewhere.

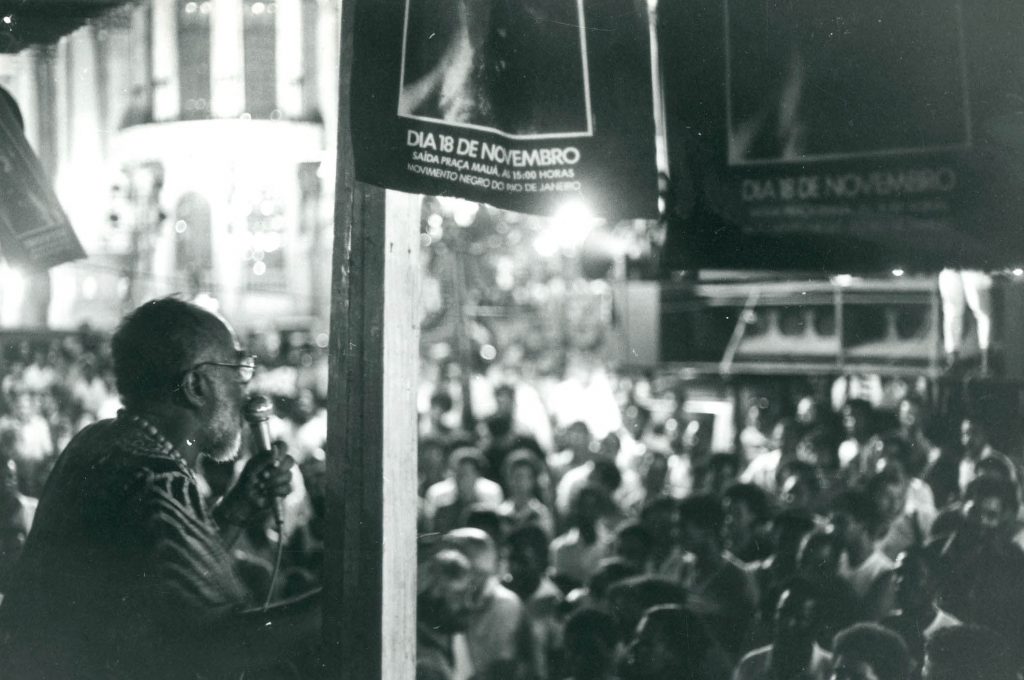

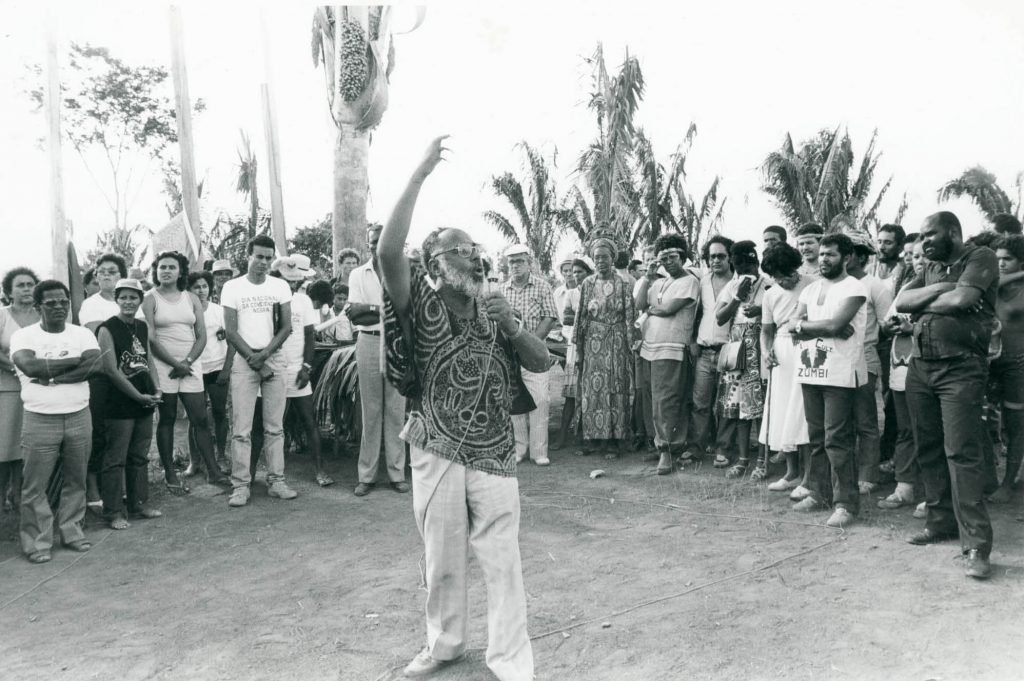

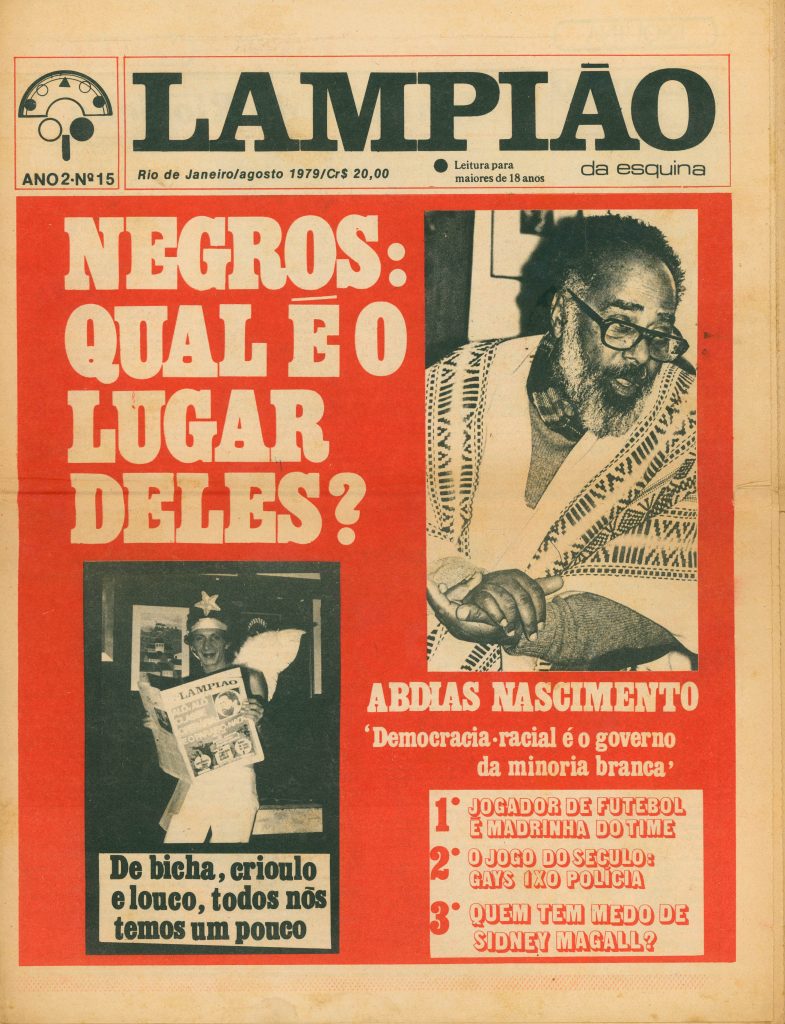

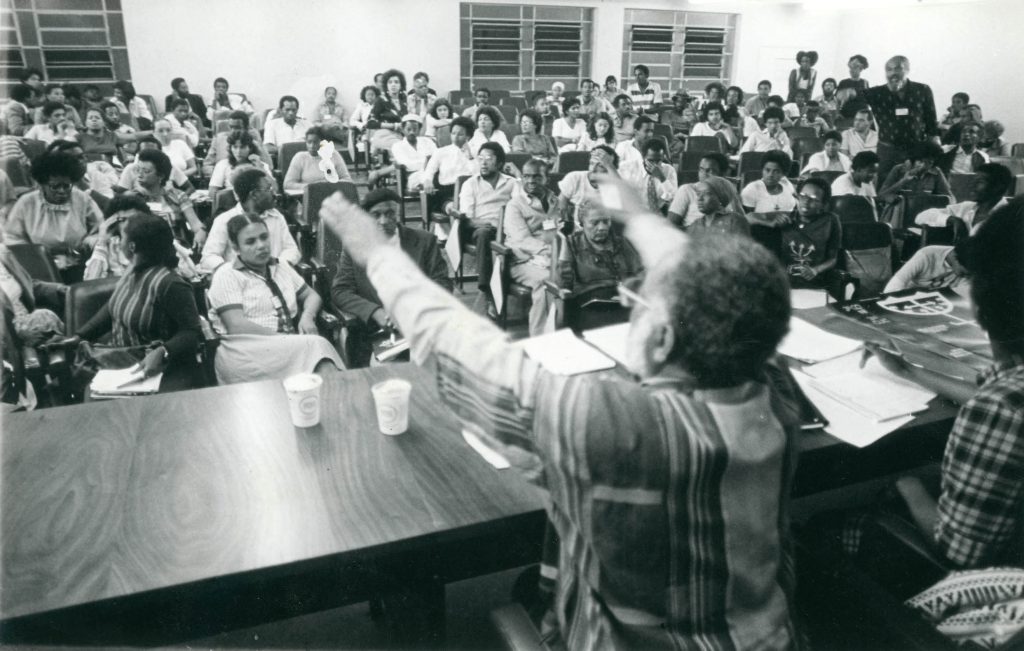

The Afro-diasporic place fell to Abdias concretely and symbolically. The election as coordinator of the 3rd Congress of Black Cultures in the Americas (Sao Paulo/SP, 1982) was the result of his “Afro-diasporic” feature of an economist and poet, playwright and political activist, fine artist and academic researcher. Abdias was an anti-racist intellectual in the physical and metaphysical senses, a fighter against the social-racial-economic and ancestral ills who attacks “other” ways of being and living that were and have been given a marginalized-inferior-folklore-like-demonized status.

Afro-diasporic knowledge lead to performative pedagogy, which does not overestimate either the single thought or the single form of knowledge transmission, but rather multiple. As Abdias prized. As ancestrally-black intellectuals-artists from elsewhere prize.

With the prospect of de-silencing the past built from the Euro-Western perspective, as proposed by Haitian historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot, there is a list below with some intellectuals contemporary of Abdias. They are playwrights, poets, writers, and artists of different languages, inhabitants of Caribbean Afro-diasporas that are missing in the Euro-Westernized historiography originating from worldviews that can hold all the worlds.

Nicolás Guillén (1902-1989, Cuba)

Poet, journalist, diplomat. Regarded as a genuine representative of black poetry in Cuba. His intense participation in the political life of his country cost him exile on several occasions. In 1937, he joined the Partido Comunista [Communist Party]. With the triumph of the Cuban revolution in 1959, he undertook greatly important diplomatic missions and visited, among other countries, Brazil, Chile, France, the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary. In 1961, the Unión de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba [Union of Writers and Artists from Cuba] (Uneac) is founded and Guillén was elected its president, a position he held until his death.

His literary output was initially included in the realm of postmodernism, with the avant-garde experiences of the 1920s. Against this backdrop, he soon became the most prominent representative of black or Afro-Antillean poetry. With a “mulatto”-culture approach in his writing, his incursion into the literary universe materialized with Motivos de Son (1930), followed by Sóngoro Cosongo: Poemas Mulatos (1931) and West Indies, Ltd. (1934) – in which he denounced the exploitation suffered by the Antillean archipelago – and with poems dispersed over various books.

Henceforth, he went deeper into his political concerns and concerns for his “brothers-in-race,” pursuing paths opened with Sóngoro, Cosongo, an onomatopoeia that shows the purpose of the poet in shaping the African-Cuban roots in rhythm and voice. His work continued defying regional and international political landscapes hostile towards the black people and the working classes.

In his political endeavor, he accepted the invitation made by poet Jacques Roumain, director of the Institute of Ethnology in Haiti and traveled as a cultural envoy of the Cuban Government, a delegate of the Frente Nacional Antifascista [Anti-fascist National Front], and journalist of Hoy, in 1942. Two years later, he founded Gaceta del Caribe cultural magazine alongside José Antonio Portuondo, Mirta Aguirre, and Ángel Augier. In 1945, Guillén set off on a trip around South America, during which he exchanged ideas with artists and intellectuals. This expanded and deepened his view of the American continent.

At the age of 80, he was awarded the doctor honoris causa degree by the University of Bordeaux, in France, and the Order of José Martí, the highest distinction bestowed by Cuba.

Marie Vieux Chauvet (1916, Haiti – 1973, United States)

Playwright and novelist. The first celebrated woman of Haitian literature whose work is marked by equality principles and, in the field of philosophy, by existentialism. Known for her strong political stance, Marie Chauvet acted against abuse of all kinds which victimize women and the disadvantaged in general.

Published by the best publishers in France, object of study by the largest universities in the United States, Chauvet chose voodoo, slavery, colonialism (internal and external), and eroticism as the main subjects of her work. She was a prominent figure in Haitian literature in the early 1960s and the only woman in a group of writers that included Davertige, Serge Legagneur, and René Philoctète. On Sundays, she would open her home to literary gatherings.

Facing her husband, who separated from her for disagreeing with her political views, and the dictatorship of François Duvalier (1907-1971), she tried to publish Amour, Colère et Folie, whose manuscript read by Simone de Beauvoir earned her an invitation to have her work published by Éditions Gallimard (a publishing house founded in 1911 and owned by one of the most influential publishing groups in France to this day). Shortly after the publication of this book in 1968, its spread was banned under threat to her and her family by the Duvalier regime. Soon after the ban, Chauvet went into exile in New York, where she wrote her last novel, Les Rapaces.

Jan Carew (1920-2012, Guyana)

Writer, historian, intellectual, professor, actor. Most of his fiction is set in the Caribbean, describing the fight of colonized Caribbeans for having defined their own identity whether being at home or in exile. His nonfiction literature focuses on related topics, including studies on the presence of indigenous and African peoples in the Americas.

Carew lived between the Caribbean, the United States, and Europe, where he joined Laurence Olivier’s theater company. He taught at universities such as Princeton (Third World literature and creative writing) and Northwestern (African-American and Third-World studies). The highlights among the awards he won are the Hansib Publication (1990); Paul Robeson in honor to “live a life of art and politics” (1998); and the Caribbean-Canadian Lifetime Creative (2003).

Sylvia Wynter (1928, Cuba)

Novelist and playwright. Born in Cuba to Jamaican father and mother, Sylvia Wynter is one of the most important contemporary writers in the Caribbean. Her work is based on the local languages of the region (such as Jamaican patois). Her many writings blend theories of history, literature, science, and black studies and explore topics such as race, colonialism, and human representations.

After a period of time in London writing radio plays, Sylvia Wynter became a lecturer at the University of the West Indies and later was a professor at the universities of Michigan and California. In 1977, she became a professor of African and African-American studies at Stanford University.

Her most widely read novel, The Hills of Hebron (1962), speaks about the crisis provoked by tensions between the spread of Christianity and the persistence of the traditional African spirituality in a Caribbean community. Most of her plays are still unpublished, including Shh … It’s a Wedding (1965); 1865, Ballad of a Rebellion (1965); and Maskarade (1979).

Edouard Glissant (1928-2011, Martinique)

Anthropologist, philosopher, poet, novelist, theorist, and essayist. Member of a generation of intellectuals from the colonies who was educated in the metropolis (France). His critical thinking on the anti-colonial struggles, colonialism, and the identity of the Afro-diasporic peoples is evidenced in his work and, with it, the development of the concepts of antilleanity and creolization. During his studies in Paris, he was an active member in the group of African and Antillean students among whom was another great exponent, fellow Martinican Frantz Fanon (1925-1961).

He took part in Marxist literary circles alongside poets and also in the International Circle of Revolutionary Intellectuals, whose purpose included a critical analysis of Marxism and a study of colonialism-related issues. For Glissant, it was up to the arts and literature to boost the identity project of different communities, with particular attention to those marked by the slave trade.

A French literature professor at the City University of New York (Cuny) for more than a decade, Glissant divided his time between the United States, Martinique, and France, where he founded the Institut du Tout-Monde in 2006. In the same year, then-President Jacques Chirac gave him the mission to foreshadow and chair the Centre National pour la Mémoire des Esclavages et de leurs Abolitions [National Center of Memory of Slavery and Abolition], an institution that is still operational.

Frankétienne (1936, Haiti)

Writer, poet, playwright, musician, activist, performer, intellectual, fine artist, and professor. Frankétienne is a key name when speaking about the language, aesthetic, political, and social dimensions of creoleness.

He authored the first novel in Haitian Creole (Dézafi, 1975, an allegory of the political oppression in the country under the dictatorship of Papa Doc, as François Duvalier became known). While also publishing in French, it was with the appreciation of Creole that his work went to the general public and changed the paradigm in literature previously dominated by the language of the old colonizers.

He has published over 30 titles to date and was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2009, and named UNESCO Artist for Peace in 2010.

Maryse Condé (1937, Guadaloupe)

Writer, novelist professor. After graduating from the Sorbonne in Paris, Maryse Condé married Guinean actor Mamadou Condé in 1960 and went on to teach in Guinea. She continued teaching in countries like Ghana and Senegal even after her divorce. Only in 1973 she returned to France with her four children. There she married Richard Philcox and began to teach at several universities while also taking up a novelist’s career.

After the publication of Ségou, her fourth novel, Maryse Condé returned to Guadaloupe, where she stayed for a short time, and eventually settled down in the United States, where she became professor emerita of French at Columbia University.

Her fictional work addresses issues about sex, races, and cultures in different places and historical periods. Since 2004, she has chaired the Comitê pela Memória da Escravidão [Committee for the Memory of Slavery), created under the Taubira Law, enacted in the same year, recognizing the slave trade as a crime against humanity.

Some of her most acclaimed novels include Heremakhonon (1976), Ségou (2 volumes, 1984-85), Desirada (1997), and Célanire Cou-Coupé (2000). Among her major essays include Pourquoi la Négritude? Négritude ou Révolution (1973) and Négritude Césairienne, Négritude Senghorienne (1974). Maryse Condé was selected for Le Grand Prix Litteraire de la Femme (1986) and Le Prix de L ‘Académie Française (1988) by her lifetime achievement.

Liliane Braga is a doctoral student in social history at PUC/SP, where she is a member of the Centro de Estudos Culturais Africanos e da Diáspora [Center for African Culture and Diaspora Studies] (Cecafro). Her doctoral thesis deals with the Western episteme counternarratives based on Black cinema in Brazil and the Caribbean.